by Kristoffer Collins-brown

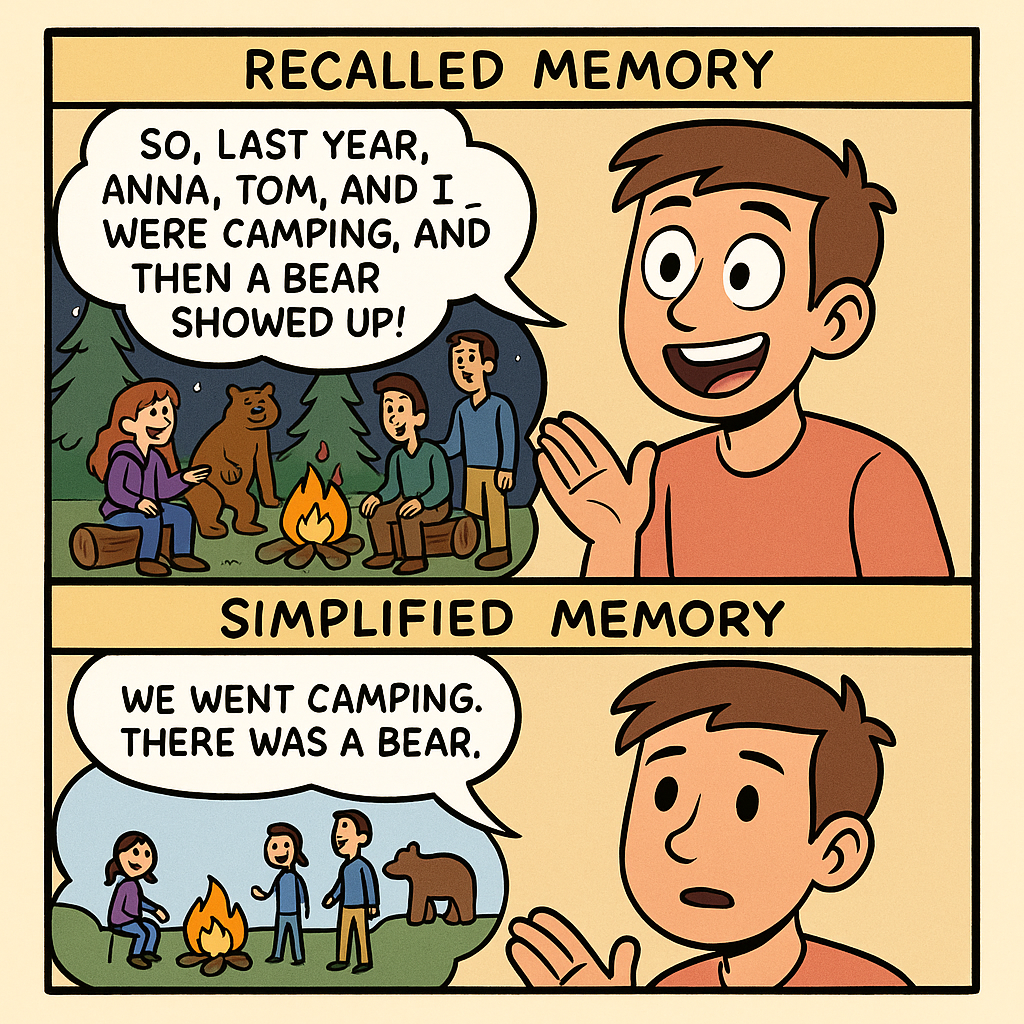

Have you ever told a story and had a fiend stop you in the middle and say ” wait, that is not what happened?” You are not the only one. Our memories are strong, yet they are also imperfect. When we remember something, we are not replaying a flawless, put in order video. Instead, we are reconstructing bits and pieces from our memory and some times we leave parts out. This is known as leveling.

Leveling is a type of memory distortion where people unconsciously leave out minor or less important details while remembering or retelling an event¹.For example, imagine your brain pressing the TL;DR (to long, don’t read) button when you try to recount a story. Let’s assume someone tells you about a wild weekend excursion where they met three individuals from various nations, tried a meal they couldn’t pronounce, and ended up traveling in a truck bed under the stars. You might relate it as: “They met a bunch of people and had some food and a crazy night.”

leveling is one of three memory distortions, the other two being sharpening and absorption. Sharpening emphasizes or exaggerates crucial aspects, while assimilation changes memories to meet our expectations, leveling is all about simplification²

When does it start?

Leveling begins in childhood. When children learn to recall and explain events, they frequently omit specifics and focus on the broad picture. This is not laziness; it is how cognitive development occurs. Our brains learn to prioritize relevance over completeness³. As we mature, this behavior becomes ingrained in how we store and access a wide range of information, from personal recollections to academic content. In fact, researchers believe leveling is a product of schema-based memory. Schemas are mental frameworks we use to understand the world. When something doesn’t fit a schema, we’re more likely to forget it or reshape it to fit our expectations⁴. In this way, leveling becomes a tool for our brain to make sense of complex, confusing life events.

My research

One of the most famous studies on memory and leveling comes from Frederic Bartlett’s 1932 experiment, The War of the Ghosts. In the study, British participants read a Native American folktale filled with unfamiliar cultural references. When asked to recall the story later, they tended to simplify it, leave out foreign elements, and change details to make it more familiar⁵.

This demonstrated that memory is not a perfect recording, but rather a reconstruction. Leveling helped participants remember and recount the tale more easily, but it also generated distortions.

How to use leveling to study

When you’re studying for a huge test or trying to remember knowledge from a lecture, your brain will naturally strive to simplify it. This can be useful—you could compress a lengthy paragraph into a brief summary that is simpler to recall. However, if you level too much, you risk missing out on important information.

Assume you’re studying psychology and learning about classical conditioning. If you remember that it contains dogs and bells but overlook the fact that the unconditioned stimulus and reaction are part of the main process, your knowledge will be incomplete.

According to cognitive research, students often level material in ways that hurt comprehension, especially when dealing with unfamiliar or complex topics⁶. In fact, when students (me as well) take notes, they frequently simplify too much, leaving out essential information that would otherwise help them appreciate the big picture.

Study smarter

Here are some tips to help study better ( Ive started to use some of these myself)

- Review regularly. When you go back to your notes or readings, you’ll catch any details that your brain might’ve “leveled out” earlier.

- Use self-explanation. Try teaching a concept to someone else. If you find you’re oversimplifying, revisit the material.

- Create concrete examples. Just like in math or history classes, using specific real-world scenarios helps you remember more than just the gist.

- test yourself. Practice questions that force you to recall deeper details, not just the broad strokes.

real world example of leveling while you’re learning

imagine a law student learning about the United States Supreme Court. Reading briefs, delivering oral arguments, collaborating, and writing opinions are all part of the process. However, after a few weeks, the student recalls it simply as “The Supreme Court decides big cases.” That’s leveling: they preserved the overall notion but removed the individual steps.

While the reduced approach may aid in general knowledge, it will not suffice to answer an exam question that requires the entire process. This demonstrates why understanding levels is especially beneficial for students: you can utilize simplification to your advantage if you know what the original concept looked like.

lets end this thing

Leveling is a memory shortcut that allows us to condense complex experiences, but it can also lead to forgetting or misinterpreting the finer details. From childhood to adulthood, our brains typically remove elements to make stories simpler to remember and share. However, when it comes to studying and learning, we must realize when we are oversimplifying.

Whether you’re studying for an exam or simply trying to comprehend new material, being conscious of levels allows you to become a more strategic learner. Consider this analogy: leveling is similar to film editing. If you remove the wrong scenes, the entire story may lose its meaning.

So, the next time you respond, “I kind of remember that,” take a moment to consider what your brain may have missed.

- Schacter, D. L. (1999). The seven sins of memory: Insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. American Psychologist, PubMed

- Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, PubMed

- Fivush, R., & Nelson, K. (2004). Culture and language in the emergence of autobiographical memory. Psychological Science, SAGE Journals

- Alba, J. W., & Hasher, L. (1983). Is memory schematic? Psychological Bulletin

- Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology. Cambridge University Press. APA PsycNet

- Kiewra, K. A. (1985). Investigating note-taking and review: A depth of processing alternative. Educational Psychologist, Taylor & Francis Online

Hello, I really enjoyed reading this blog since it relates to struggles that I face still even though I am no longer a first-year student. I especially enjoyed the dog and bell example it really showed how our minds while benefiting us by summarizing long worded writings can also cause a huge obstacle when it levels too much to the point a lot of key components are missing and the information you remember no longer has any benefits. I never quiet understood why my brain did that but your blog post defiantly explained it nicely.