By Ethan Blackowicz

Introduction

You’re feeling on top of a course- You don’t need to do anything else, procrastinating on studying before the night of an exam because it’s easy to remember. You feel the answers coming to you so easily, and feel on top of the world…and then the grade comes back, and it’s a D. How does this happen? You look at the course material, and realize tiny differences here and there. Sometimes you might recall these differences, and inwardly sigh for not remembering them in the moment, but other times you might not even recall seeing this information. This effect is called the misinformation effect. A method in which the brain tricks itself over time, with the original memory of happenings being distorted by new experiences.(4) It sounds wide-ranging, and it is.

The Misinformation Effect

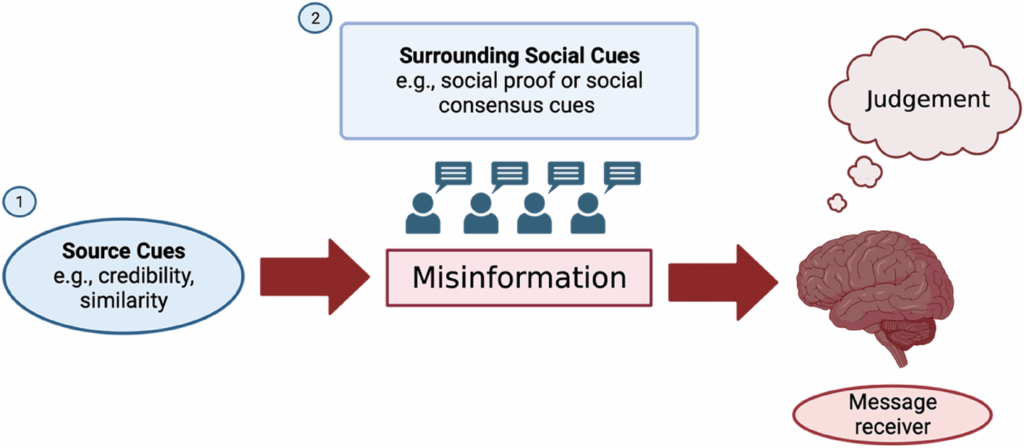

While it’s complex, the misinformation effect is easily portrayed. Let’s say two cars hit one another, and you saw the accident. If I asked ‘How did the two cars hit one another’ you’d probably remember it the same, but if I asked ‘How did the two cars wreck into one another’ the assumption becomes that the accident was more intense than what’s remembered.

In this method, the actual information retrieved is rewritten a little bit to fit with the question asked. It’s not immediately apparent in most cases, even (perhaps especially) to the person who just adjusted their view and answered the question. But if the faulty information is continually sourced to answer questions that focus on how damaging the accident was, it begins to completely adjust the perception of the event. Even if two cars bumped into another and did about 500 dollars of damage in total, but someone is continually asked exaggerated questions, they might remember bent steel, shattered windows, fire, a high speed collision, et cetera.

Similarly, this is why eyewitness testimony is so unreliable; Someone might be directly involved with an incident, or otherwise close enough to see everyone involved, but when it comes time to actually share that information, an investigator asking ‘Do you think this person would do this’ versus ‘Does this person look like a criminal’ can create completely different recollections of the event, sometimes even reframing their own recollection of the event to include the person accused of committed the crime to begin with.

Of course, these are dramatic examples. But the brain can do this to itself easily, even on a much smaller scale. Just saying “I know the course information” and repeating it back to the best of your ability without refreshing it through something like the course materials, or even something like a Google search, means you might remember something completely different when taking a test or doing a project. Especially if you have other things going on in life, or potential distractors in the middle of your mental study session.

How to Avoid Misinformation

The solution used by a lot of people is actually fairly simple: Taking notes. Writing down the information immediately after experiencing an event helps in retaining the correct memory of it, with minimal distortion(5). While this helps reduce the effect, it doesn’t entirely remove false memories. For those, they usually take deeper consideration and the ability to realize they’re wrong to begin with. While it’s more difficult to train critical thinking skills, it’s best to call the memory into question sometimes- thinking “Was this how it went” or “Is this the answer” and recalling more memories can be incredibly helpful!

Outside of this, reviewing the course material and ‘refreshing’ the memory can also help a lot- A memory can change, but books and details within rarely change. Similarly, looking at any documentation, electronic or otherwise, can help someone remember due dates, schedules, or anything else. Though, the standard structure of school helps with this quite a bit too. Every time someone does homework, they’re actively recalling and comparing the information in their brain and using it, and the more that information is repeated, the more one can reference not just one past memory for that information, but multiple which correlate to one another, and keep the form of that information reinforced.

However, it’s important to realize that it’s going to be impossible to fully avoid misinformation. If you recall a childhood memory, that memory is going to be distorted from the original no matter what. And similarly, while you can refresh memories, there will always be at least some form of degradation over time. Regardless, when it comes to easily-avoided mistakes that cost you, it’s best to refresh anyways beforehand.

- Swire-Thompson, B., Miklaucic, N., Wihbey, J. P., Lazer, D., & DeGutis, J. (2022). The backfire effect after correcting misinformation is strongly associated with reliability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(7), 1655–1665. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001131

- Greenspan, R. L., & Loftus, E. F. (2020). Eyewitness confidence malleability: Misinformation as post-identification feedback. Law and Human Behavior, 44(3), 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000369

- Gurney, D. J., Pine, K. J., & Wiseman, R. (2013). The Gestural Misinformation Effect: Skewing Eyewitness Testimony Through Gesture. The American Journal of Psychology, 126(3), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.3.0301

- Loftus, E. F. (1979). The Malleability of Human Memory: Information introduced after we view an incident can transform memory. American Scientist, 67(3), 312–320. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27849223

- Loftus, E. F. (1992). When a Lie Becomes Memory’s Truth: Memory Distortion after Exposure to Misinformation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(4), 121–123. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182152

Hi Ethan, I enjoyed your post as I am one of many who have fallen for the misinformation effect. Sometimes names, dates, and places can get all mixed up in my head which clearly contributes to this feeling. You pointed out that generally note taking can aid in avoiding the misinformation effect, and I’ve certainly found benefits in physical note taking. What strategies to you use in your academic work to “keep your facts straight”? The suggestibility of memory is an interesting topic and it’s fascinating to see the phenomenon at play in our everyday lives. Overall, your post was helpful in understanding an interesting shortcoming of human memory.